Bringing the Science of “Learning” Into Focus

The Science of Reading movement has brought so much change to our schools over the past few years—new curriculum, new resources, decodable readers replacing leveled books and even swapping old assessments that have been used for the past 20 years…for brand new ones.

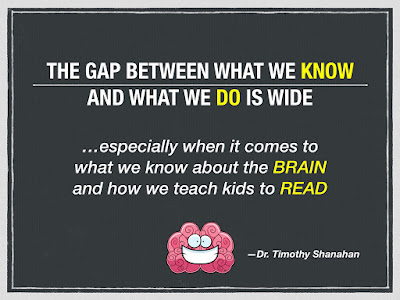

Dr. Mark Seidenberg reminds us in his Yale Child Study Center Talk, Where Does the “Science of Reading” Go From Here? that we still have work to do to effectively incorporate these principles, practices and research.

And to effectively incorporate this research, we need to focus on not only effective teaching, but on effective learning. So how might the science of learning inform our practice?

My name is Leah Ruesink, and I’m an early literacy specialist, district trainer and adjunct professor from Michigan. In my previous post, I discussed how UFLI Foundations and Secret Stories belong together as the “backbone” and the “lifeblood” of science of reading-based instruction.

In this post, I want to dive deeper and discuss some common misconceptions/assumptions about the “Science of Reading,” using points adapted from Dr. Seidenberg’s talk.

Things to Keep in Mind:

- We need more research on translating science to classroom practice.

Mark Seidenberg (2023) reminds us, we still have work to do to effectively incorporate these principles, practices and research. We need more “science” in the “Science of Reading.” - We need to admit what we don’t yet know, resisting the creation of new dogma.

“Thinking like a scientist involves more than just reacting with an open mind. It means being actively open-minded. It requires searching for reasons why we might be wrong—not for reasons why we must be right—and revising our views based on what we learn.” —Adam Grant - We need to learn more about what works for who (and under what conditions).

Equitable instruction applies to all learners, including the significant proportion of children who are often neglected as the focus of reading research—those who learn to read accurately and efficiently in advance of formal reading instruction.

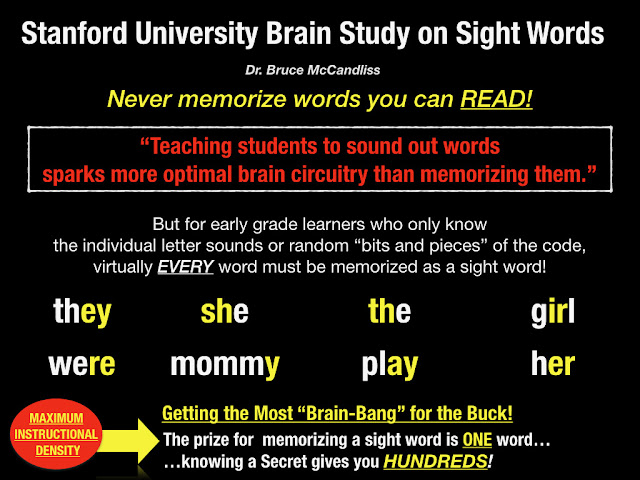

1. Does everything need to be taught in order for students to learn?

The Assumption→ Good phonics instruction is always explicit.

Explicit instruction is crucial. But what about implicit learning?

Our brains are not wired to learn to read naturally, like we learn to speak; therefore explicit instruction is necessary….especially for our learners with the greatest needs. But what about implicit learning— does it have a place in our reading classrooms?

Well of course!

“Much, if not most, of what children learning to read in English come to know about its orthographic phonological relationships, is acquired through implicit learning.” —Hoover & Tunmer (2020).

For example…

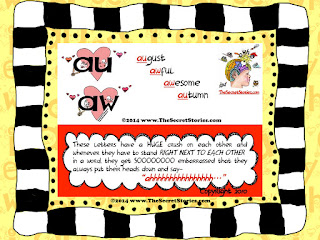

Let’s say that you explicitly introduce your students to the /ph/ Secret Story (below). Then ten minutes later, Phoebe is underlining the /ph/ at the beginning of her name and using it to write the word phone. Later that afternoon during reading block, she exclaims, “Look, I see the /ph/ Secret in word Ralph in our book! He has the same Secret in his name that I have in mine!”

With just a couple minutes of explicit instruction, this student is already applying the skill to implicitly read and write new /ph/ words.

As Seidenberg (2023) explains:

“Explicit instruction is there to scaffold statistical/implicit learning. But only as much as needed and not one bit more.”

Secret Stories embrace both explicit and implicit learning

- Grounding phonics skills in feelings, emotions, and behaviors that children already know and understand.

Early brain development occurs from back to front, with the affective, or “feeling-based” networks (which regulate the implicit behaviors that kids understand and recognize) developed long before the higher-level, executive processing centers are formed. Secret Stories takes advantage of these earlier-developing networks by connecting letter-behavior to kid-behavior to make phonics sounds more predictable. Sneaking abstract letter sound skills through the brain’s “backdoor” by connecting them to what kids already know and understand makes them easy to learn and remember.

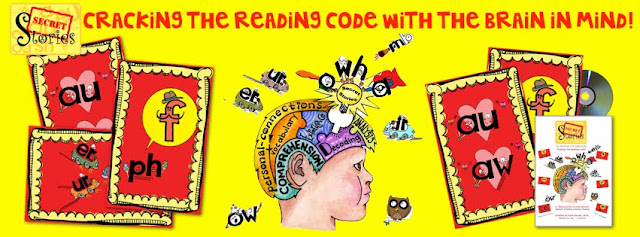

Secret Stories uses evidence-based embedded mnemonics

Using a simple, story-based delivery system, Secret Stories explicitly teaches the phonics patterns and their corresponding sounds, each of which is depicted with embedded mnemonic images to help kids remember and apply them. It is through this visualized, phonics framework that beginning learners can independently recall the sounds they need for reading and the spelling patterns they need for writing. In this way, the embedded mnemonics do the “heavy lifting” by helping kids keep track of which letters make what sounds. This is critical because while the sounds are made predictable by the Secrets, the phonics patterns that go with them are not. It is only through students’ ongoing reference and use of the embedded mnemonics to read, write and make sense of text throughout the day that these sound-symbol connections become orthographically mapped in the brain. Until then, Secret Stories embedded mnemonic sound wall provides the clear and “concrete” connections that beginning and struggling learners need to read and write independently .

For example….

Let’s say that you previously shared the ay/ey Secret phonics pattern to help kids decode the days of the week on the morning calendar. Later, they notice the same /ay/ Secret in words that are in the morning message and immediately recognize it as something they already know.

Because they explicitly learned the letters that make the sound, think of all the words they’ll be able to learn implicitly! Not to mention the /or/ Secret they also know and the many more words that it unlocks.

2. Is it possible to have too much of a good thing?

The Assumption→ Not all learners need the extra phonics practice, but it’s not harmful. At worst, it’s just additional practice with essential skills.

I’ve always responded in agreement to this assumption. Extra practice certainly does not feel harmful…and in fact, extra practice is absolutely necessary for some students who are in great need of reading support.

Is it possible to have too much of a good thing? Of course! The clock is ticking. The goal is to get in, get out, and move on.

—Seidenberg, 2023

“SoR structured literacy is a prodding approach, with low expectations about rate of progress” (Seidenberg, 2023). Consider the range of student abilities and skills in a kindergarten or first grade classroom. In February, you may have some students working on blending CVC words like “cap” and “sit” and others reading multisyllabic words! Yet, many of us spend 90 minutes or more every day teaching/ providing center work for a phonics skill that is either too difficult or way too easy for the majority of our students! Consider for a moment… if there is a way to give ALL learners earlier access to the codee they need to make sense of the words they see everyday …WOULD YOU WAIT?

Whereas teaching a skill requires readiness to learn, sharing stories holds no expectations. They simply linger in the brain, “incubating” the information and ideas they contain, particularly that which is meaningful to the listener. and ideas they contain. While all students benefit from this early incubation time, it’s those who struggle that benefit from it the most, as they require the most time to learn and apply new skills.

Secret Stories provides differentiated access to the code

For example….

Let’s say a student in your class is trying to write the word “house” but the ou/ow phonics pattern isn’t on your grade level scope and sequence. Would you just tell them, “I’m sorry, but you’ll need to wait until next year to learn how to read/spell the word house. In the meantime, you’ll just have to copy/memorize it.” What if there was a way for them to READ and WRITE that word now, as well as hundreds of other word with that sound?

“If you give a mouse a cookie, he’ll eat it” …and if you give kids the CODE, they’ll USE it!

We are moving way too SLOW in delivering the code kids NEED to read and write, despite how easy it is to give MORE sooner!

This can be seen in the prek/transitional kindergarten writing sample up above. Despite not having yet fine-tuned the different spelling choices, the sound-symbol relationships are clearly established, as evidenced by their use. As beginning learners gain more text experience through reading, they gain more natural insight into spelling and which patterns are correct to use in which words. Reading is by far the best teacher, and not just for spelling, but for everything, from vocabulary to comprehension. Reading is also the best way to practice, reinforce and expand phonics knowledge, that is, assuming one has enough phonics skills to read.

And herein lies an inherent roadblock for beginning and struggling readers who possess too little of the phonics code they need to read, and thus, are able to take only limited value away from daily reading and writing activities. Without advanced access to the code, it’s not possible for kindergartners and first graders teachers to keep pace with the words they see and are expected to “read” every day. Even words that are in the reading/phonics curriculum are often leaps and bounds ahead of the phonics skills that it’s teaching them.

While formal, grade-level programs and curriculums must adhere to a slower, more structured, grade-specific pace for phonics skill introduction, Secret Stories does not. That’s because Secret Stories is NOT a phonics program or curriculum, nor is it a supplement to one as there are NO lessons or activities to do. The Secrets are simply mnemonic tools to help speed-up access to the code so that kids can actually read the words they’re looking at every day in the classroom.

Click here for the Better Alphabet™ Song to automate individual letters and sounds in 2 week – 2 months and click here to read the research on simultaneous skill acquisition via the melodic mnemonic.

Dr. Seidenberg also cautions that “SoR structured literacy is a plodding approach, with often too low expectations about the rate of progress.”

The Matthew Effect on Reading Gains

The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Poorer

The more of the code kids have, the more words they can read. The more they read, the more phonics practice they get, and the better reader they become. In contrast, the less phonics skills kids have, the less words they can read and the less practice they get, decreasing the likelihood of reading success.

- The More Kids Bring to the Table, the More Value They Take Away

Using the Secrets to fast-track more of the phonics code sooner helps maximize the effectiveness of the existing reading/phonics curriculum because kids can actually read the words that are in it. It also increases the instructional value of all other reading and writing activities that occur across the day in other content areas. - The goal of the game is to GET KIDS READING!

To do this, kids need advanced access to more of the phonics code sooner, and teachers need to avoid any roadblocks in their instructional path that don’t go toward this end!

3. Is heavy phonics work actually effective for students? What about with multilingual learners and different dialects?

The Assumption→ “Significant time should be spent in the classroom teaching students complex phonics terminology and rules.”

While teaching kids complex phonics rules may sound helpful (in line with explicit instruction), the focus should be on efficiency……getting kids to actually READ the words.

Seidenberg reiterates that “the goal is to facilitate cracking the code, not teaching the code. “The goal of instruction is for [the] child to learn what there is to learn – how the code works – and to gain enough basic facts to enable reading simple texts with decreasing reliance on external feedback” (Seidenberg, 2023).

Dr. Seidenberg also expresses this concern in his earlier 2022 Reading Matters article: “Phonemes, onsets and rimes, inflectional and derivational morphology, relative clauses, collocations, and other basic components of language….Does a child need to know these concepts? I shudder when I see words like “phoneme” and “orthography” being used in teaching 6 year olds. […..] I also think it’s folly to devote precious time to teaching children the “correct” pronunciation of (all 44) phonemes prior to moving on to reading” (Seidenberg, 2022).

Other well-known researchers have also expressed that the goal of good phonics instruction is to advance reading, not to teach “rules for rules-sake.”

“The point of phonics isn’t to provide readers with exactly correct pronunciations of words, but only “close approximations” —Dr. Ann Cunningham

Phonics instruction should tip students off to some of the more frequent and useful orthographic patterns, but it should never attempt to impart them all.” —Dr. Timothy Shanahan, 2022

Secret Stories removes the complexity

- When we are teaching these complex rules we have to ask…”What is this for? Does it help them READ or SPELL words? Is the phonics vocabulary/terminology necessary in order to advance the reading or spelling of the words?

- Using high-level, abstract terminology is not the best, fastest route to connect with young learners who are “concrete-level” thinkers, nor is it most helpful for older struggling readers who often have issues with language processing and working memory.

- At the level it’s being discussed, it’s simply not needed (e.g. kids don’t need to know there is a “diphthong” in the word how, or that there is an “r-controlled vowel sound” in the word her in order to read and spell those words). Adding unnecessary complexity only serves to delay access to these critical pieces of the code that could otherwise be easily given at the kindergarten. The goal is for kids to be able to use the phonics patterns to READ and SPELL, not to identify the phonics category into which they fall.The video below shows a beginning kindergartner easily recalling these “r-controlled vowel” sound/spellings, even though most reading/phonics curriculums don’t formally introduce them late first or early to mid second grade. WHY WAIT?

Secret Stories provide efficiency AND engagement

- When you align phonics “rules” to letter behavior, everything becomes much easier because kids can logically deduce the “most and next most likely” sounds. This, in turn, helps support facilitate and support the cognitive flexibility needed for advanced decoding. Without cognitive flexibility, learners are left to identify words based on “rules and exceptions,” and this includes the need to memorize easily decodable “heart words” at the beginning grade levels.

“Recently, there has been a great deal of correlational investigation into the importance of cognitive flexibility in decoding. Enough convincing, high-quality work to conclude flexibility to be an essential property of proficient decoding ability. Kids who lack that kind of flexibility are at a disadvantage.” —Dr. Tim Shanahan (2022)

- Imbuing the Secret Stories strategies into existing reading/phonics curriculum helps kids to become flexible decoders, using the Secrets they know to figure out new words. The video below shows first grade ELL students applying their “phonics flexibility” as they ponder the spelling of the word light after having already successfully decoded the word. The critical thinking playground that emerges from their conversation shows how adept even beginning and inexperienced learners be in using what they know to logically predict the “most and next most” likely sounds of letters.

Teaching phonics isn’t rocket science, nor should it be given that the “end-user” of our instruction is a 5 year-old who is likely to be licking the carpet and eating his shoe! And yet, we can still give him enjoy easy access to the code he needs to read, and delivered in a way that makes perfect sense.

Secret Stories provides teachers with “deliverable buckets” to get phonics knowledge to the “end users”

Aligning phonics instruction with the Science of Reading requires not only understanding how the brain learns to read, but how the brain actually learns. Understanding the nexus between the “science of reading” and the “science of learning” provides insight into how we can deliver phonics faster and make skills more accessible to all learners, and from the earliest possible grade levels.

“Neuroscience carves a clear path, but it is up to us to head its message.”

—Dr. Kurt Fischer

Follow Leah Ruesink @TheEarlyLiteracyCoach on Instagram for more on Secret Stories and the Science of Reading, and continue the conversation in the Science of Reading Meets Science of Learning Group on Facebook!

Join the conversation in the Science of Reading Meets Science of Learning Group on Facebook and follow Leah Ruesink on Instagram at @TheEarlyLiteracyCoach on Instagram.

Hopefully this helps clear up some of the differences, but if you have any questions, please send them my way—

Hopefully this helps clear up some of the differences, but if you have any questions, please send them my way—